The commander-in-chief. If you wear a U.S. military uniform you know the person who has that title is ultimately your boss. It is something that is uniquely wonderful about the United States. The founding fathers, at the strong urging of George Washington, intentionally designed for the military to be controlled by a non-military leader.

Throughout our country’s history, there’s been a lot of debate about whether or not military service makes for a better commander-in-chief. Would military service make a president wiser on the use of military force? Or would a president who has not served in the military be better because they would listen more to the advice of their military joint chiefs?

Whatever side of the argument you sit on, here’s USAMM’s list of presidents who served in the military.

George Washington

Our list of presidents who served in the military naturally starts off with George Washington. He served in the Virginia militia and the Continental Army rising to the rank of general. He fought in the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War and he became the first president of the United States.

Thomas Jefferson

In 1770 Virginia’s governor appointed Jefferson to lead his county’s militia in the rank of colonel. During the Revolutionary War Jefferson was responsible for providing militia soldiers as replacements for the Virginia regiments of the Continental Army. He saw no action. Jefferson became the third president of the United States in 1801.

James Madison

In 1775, after serving briefly as a private, Madison was commissioned as colonel and commander of the Orange County Regiment, Virginia Militia. Madison was responsible for the training and readiness of his regiment, but his frail health prevented active service. Madison was inaugurated as the fourth president of the United States in March 1809.

James Monroe

In 1776, Monroe left college joined the Virginia militia in the Continental Army. After his training and commissioned as a lieutenant, Monroe was a part of the surprise attack on a Hessian encampment at the Battle of Trenton and he nearly died from battle wounds (severed artery). He was at the encampment at Valley Forge and served in the Battle of Monmouth. He rose to lieutenant colonel in the militias and became the fifth president of the United States.

Andrew Jackson

Jackson served in the War of 1812 as part of the Tennessee militia and he fought two campaigns against the Creek Indians in the winter and spring of 1813. In 1814, Jackson was commissioned a major general in the Army of the United States to fight the British at Pensacola and in New Orleans. He soundly defeated the British and went on to become the seventh president of the United States in 1829, and one in our list of presidents who served in the military.

William Henry Harrison

Harrison joined the Army in 1791 and after serving in the Northwest Territory, he resigned from the Army in 1798. During the War of 1812, Harrison was appointed as a major general with the Kentucky militia and later became the commander of the Army of the Northwest. He recaptured Detroit in the fall of 1813 and defeated the British on the Thames near Ontario. He became the ninth president of the United States in 1840.

John Tyler

In 1813, Tyler joined the Virginia Militia as a captain and his company was ordered to Williamsburg, Virginia to resist the advancing British. When the British withdrew, Tyler and his men returned home. John Tyler became the tenth president of the United States in 1841.

James K. Polk

Polk was appointed as captain in the Tennessee Militia in 1821 where he would later rise to the rank of major. He is often credited with being a colonel, but the National Guard Bureau states he was a major. He would become the 11th president of the United States and one in our list of presidents who served in the military.

Zachary Taylor

Taylor served in the U.S. Army for four decades and was the first president to have spent his life in military service before entering politics. He commanded troops in the War of 1812, the Black Hawk War and the Seminole Wars. He also served in the Mexican War. He was elected president in 1848, becoming the 12th president of the United States.

Millard Filmore

Fillmore became the 13th president of the United States, rising to the presidency from vice president after Zachary Taylor died a little more than a year after taking office. Filmore served in a New York militia during the Civil War, but saw no action. He rose to the rank of captain, but because his service records are scarce, some sources state he was a major in the militia.

Franklin Pierce

In 1831, Pierce was appointed a colonel in the New Hampshire militia, but the Mexican War took him into the U.S. Army as a brigade commander where he rose to the rank of brigadier general. He participated in numerous engagements in Mexico and legend has it he had a bullet hole in the brim of his hat, but his military service was plagued by rumors of cowardice and injuries (a knee injury and diarrhea) that kept him from the battlefield several times. Nonetheless, in 1853 he became the 14th president of the United States.

James Buchanan

Buchanan is one of four presidents to rise to the post of commander-in-chief from the enlisted ranks. He served in the War of 1812 as a private in the Pennsylvania militia having joined in 1814. He joined the cavalry and rode to Baltimore to aid in the battle against the advancing British forces. Buchanan was one of 10 men who volunteered for a secret mission, a raid to round up additional horses for mounted militia units. After the British were driven from Baltimore, Buchanan's company was dismissed. Buchanan became the 15th president of the United States in 1856, and one in our list of presidents who served in the military.

Abraham Lincoln

A little known fact is that Abe Lincoln served in the Illinois militia and served in the Black Hawk War as a captain. What likely makes his service unremarkable is that he saw no action and he and his men returned home when they realized they would not be utilized in the war. In 1861, he became the 16th president of the United States and he would later be assassinated in 1865.

Andrew Johnson

Served as a brigadier general in the Union Army during the Civil War, but saw no action. He was appointed as the military governor of Tennessee by Lincoln and managed reconstruction efforts. He became the 17th U.S. president after Lincoln was killed early in his second term. Johnson would later become the first president to be impeached.

Ulysses S. Grant

Grant is known for commanding the Union Army in the Civil War, but he also served with distinction in the Mexican War as a junior officer. He rose to the rank of general of the Army and became one of only two five-star generals to become president. He is also the first West Point graduate to become president. He became the 18th U.S. president in 1869 and one in our list of presidents who served in the military.

Rutherford B. Hayes

Was commissioned as a major in the 23rd Ohio Infantry at the onset of the Civil War. He was wounded in action four times during his war service and in 1863 he was promoted to colonel after his troops helped stop confederate raiders in Ohio. In 1864, Hayes was wounded for the fourth time in the Battle of Cedar Creek and after the battle he was promoted to brevet brigadier general and eventually brevetted a major general of volunteers. Hayes became the 19th president in 1877.

James Garfield

In 1861, Garfield was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the 42nd Ohio Infantry and reported to Kentucky where he was placed in command of the 17th Brigade. At the Big Sandy River his troops were outnumbered five to one but held until reinforcements arrived. Garfield then attacked the confederates at Middle Creek, Kentucky, and won after a five-hour battle. He was promoted to brigadier general and assigned to the 20th Brigade in Tennessee. Garfield reached Shiloh on the second day of the battle and helped drive back the confederates. For his actions at the battle of Chickamauga, Garfield was promoted to major general of Ohio Volunteers. James Garfield became the 20th president of the United States in 1881.

Chester A. Arthur

Served as a judge advocate in the New York militia, but during the Civil War he became the quartermaster-general. In 1862, he was promoted to brigadier general. Arthur became the 21st president in 1881.

Benjamin Harrison

An attorney by trade, in 1862, Harrison put on a uniform was promoted to colonel and given a regiment to command from the 70th Indiana Infantry. He saw action at Russellville, Kentucky and spent the next fifteen months in Kentucky and Tennessee with his regiment. In 1864, he fought with Sherman's army and in the Atlanta campaign. The unit saw its fierce fighting in Georgia. After the Battle of Nashville, Harrison was brevetted brigadier general but in May 1865, he received his commission as brigadier general and was honorably discharged a month later. Benjamin Harrison became the 23rd president of the United States in 1889, and one in our list of presidents who served in the military.

William McKinley

McKinley joined the Army as a private at age 18 during the Civil War. Years later he would serve as commander-in-chief during the Spanish-American War. During the Civil War he served with the 23rd Ohio Volunteers and rose to the rank of captain. On one occasion, as a commissary sergeant at the battle of Antietam, he drove a wagon of hot rations to his troops during battle. As a captain and aide-de-camp in the Shenandoah Valley, he galloped under fire to give an independent regiment the word to fall back. He left military service with a brevet commission of major. In 1897, McKinley became the 25th U.S. president, the third enlisted man to do so.

Theodore Roosevelt

Roosevelt was appointed a second lieutenant in Company B, 8th Regiment, New York National Guard in 1882 where he served for four years and left as a captain. He served in the U.S. Army as a colonel in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. He is the only president to receive the Medal of Honor which was presented posthumously in 2001. He became the 26th president of the United States in 1901.

Harry S. Truman

Truman joined the Missouri National Guard on June 14, 1905 as a battery clerk serving for about a year, separating as a corporal. However, when the United States entered World War I, he reenlisted in the National Guard and became a first lieutenant in the field artillery. In August 1917 his unit became part of the Regular Army as the 129th Field Artillery of the 35th Division. Truman commanded Battery D. Truman was discharged from the U.S. Army as a captain in 1919. He became 33rd president of the United States in 1945 and another man hailing from the enlisted ranks to reach the military’s top post.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Eisenhower is the second West Point graduate and second general of the Army (five-star general) to serve as president of the United States when he became the 34th U.S. president. He graduated West Point in 1915 and spent much of World War I stateside in training assignments. Eventually his unit was mobilized and sent overseas, but he never saw action because the Armistice was signed. He spent much of his military career as a planner which aided him considerably. From 1941 to 1944, he rose from the rank of colonel to five-star general. In 1943, he was appointed Supreme Commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces and he commanded Operation Overlord. Two years later, he accepted surrender from Germany and became the Army’s chief of staff retiring in 1948 from the Army. He is probably one of our most known presidents in uniform.

John F. Kennedy

Kennedy served in World War II in the U.S. Navy Reserve for four years starting in 1941. He rose to the rank of lieutenant and commanded a PT (patrol torpedo) boat in the pacific in the Soloman Islands. He completed more than 30 missions and in 1943, he was steering his boat to attack a passing enemy destroyer when he was rammed by a Japanese ship. He and his crew swam several miles to an island where they were stranded for a week. Kennedy injured his back in the attack and he earned the Purple Heart. He became the 35th president and one in our list of presidents who served in the military. In November 1963 he was assassinated by a former Marine, Lee Harvey Oswald.

Lyndon B. Johnson

Johnson served in the U.S. Naval Reserve and rose to the rank of commander. He joined the reserve in 1940 as a lieutenant commander (he was a congressman at the time). In 1942, he proceeded to the pacific for inspection duty. Johnson was awarded the Silver Star by Gen. Douglas MacArthur. The citation reads: “For gallantry in action in the vicinity of Port Moresby and Salamaua, New Guinea, on June 9, 1942. While on a mission of obtaining information in the Southwest Pacific area, Lieutenant Commander Johnson, in order to obtain personal knowledge of combat conditions, volunteered as an observer on a hazardous aerial combat mission over hostile positions in New Guinea. As our planes neared the target area they were intercepted by eight hostile fighters. When, at this time, the plane in which Lieutenant Commander Johnson was an observer, developed mechanical trouble and was forced to turn back alone, presenting a favorable target to the enemy fighters, he evidenced marked coolness in spite of the hazards involved. His gallant actions enabled him to obtain and return with valuable information.” The other crewmen on board did not receive any awards and interviews with the crew members reveal that the plane was never attacked. One month later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a directive that national legislators could not serve in the armed forces. Johnson went on to become the 36th president and often wore his Silver Star lapel pin.

Richard M. Nixon

Nixon served in the U.S. Naval Reserve during World War II, joining in 1942 and rising to the rank of commander. In 1943, he was assigned to the south pacific as a logistician, commanding forward detachments. He left active duty in 1946, resigning his commission, but remained in the reserve until he retired from it in 1966. He became the 37th president of the United States, and one in our list of presidents who served in the military.

Gerald Ford

Ford served in the Naval Reserve during World War II as a lieutenant commander for four years joining after the Pearl Harbor attacks. He joined the USS Monterey where he served as an assistant navigator and antiaircraft battery officer. His ship saw action in the Pacific theater and Ford helped take several islands, participated in supporting carrier strikes and he supported several beach landings. He earned nine campaign stars on his Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal. He left service in 1946 and became the 38th president of the United States.

Jimmy Carter

Carter served in the U.S. Navy after graduating from the Naval Academy in 1946. He became the 39th U.S. president. In 1948, he began submarine duty and served aboard the USS Pomfret and later served on the USS Barracuda. Carter planned to enter the Navy’s nuclear power plant operation and be one of the first crewmen aboard America’s first nuclear subs, but his father died and he requested a release from active duty to tend to his father’s peanut farm. He left the Navy in 1953 and served in the inactive reserve until 1961.

Ronald Reagan

Reagan enlisted in the Army Reserve in April 1937 as a private assigned to Troop B, 322nd Cavalry in Des Moines, Iowa. He was appointed second lieutenant in the Cavalry later that year. When World War II broke out, Reagan was ordered to active duty in April 1942 and due to eyesight difficulties, he was classified for limited service only, which excluded him from serving overseas. He served in California as a liaison officer and transferred to the Army Air Forces Public Relations team. Eventually, he joined the 1st Motion Picture Unit in California and he remained a part of the military’s public relations and movie apparatus until he separated from active duty in December 1945 and his unit created some 400 training films for the Army Air Forces. He was the 40th president.

George H.W. Bush

Bush served as a U.S. Navy pilot in World War II and rose to the rank of lieutenant j.g. He entered the Navy in 1943 and in 1944 he shipped out to the Pacific theater where he flew Avengers. He participated in numerous missions but on one mission his aircraft was downed by enemy fire. Bush managed to bail out but his two crewmates did not. He was picked up in the ocean after floating in open water for four hours. He earned the Distinguished Flying Cross. Bush was released from active duty in 1945, but was not formally discharged from the Navy until 1955 as a lieutenant. Bush flew 58 missions, completed 128 carrier landings, and recorded 1228 hours of flight time. He went on to become the 41st president.

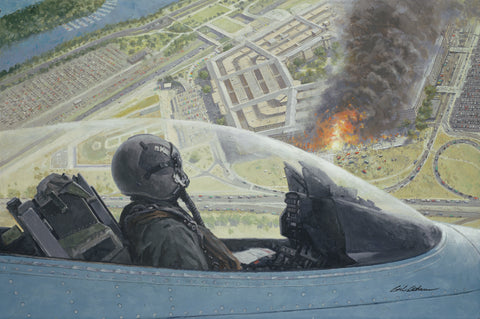

George W. Bush

Unlike his father, Bush served in the Texas Air National Guard and not the Navy, and he also served stateside during war, while his dad had served in World War II. Like his father, he was a pilot and joined the Air National Guard in 1968. He trained at Moody Air Force Base and learned to fly the F-102. He was on active duty to learn how to fly and then spent the rest of his years in uniform in the part-time military. His military service came under scrutiny in 2004 during the elections. He became the 43rd U.S. president and one in our list of presidents who served in the military.